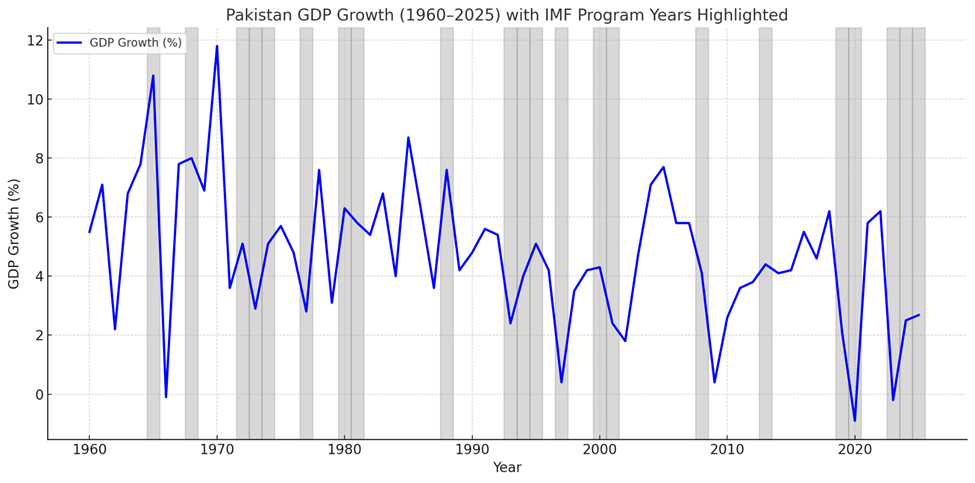

Pakistan has successfully stabilized its economy after mustering considerable effort during a grueling three-year period, which followed the multilayered crisis of 2022-23 that had causal factors ranging from domestic political friction to the global fallout of the Russo-Ukrainian War. Pakistan’s strong turnaround is best expressed in the massive improvement in credit default swap (CDS) spreads on its sovereign debt, implying that worst fears of three years ago have abated entirely. This substantial stabilization effort would not have been achieved without the Extended Fund Facility (EFF) provided by the IMF, but the IMF program was accompanied by exacting demands for serious macroeconomic reforms under an austerity paradigm. This was justified as a necessary bitter pill for structural improvements, without which the economy would likely have lapsed into acute disrepair. Yet it is precisely this risk of disrepair that remains a cause for concern among economists. Once the current program concludes, is Pakistan at risk of falling back into its old ways? This concern is legitimate and circumscribes a longstanding tendency that might be termed the borrow-bust cycle. According to this pattern, our approach proceeds as follows: a crisis emerges and Pakistan rushes to the IMF; the IMF imposes austerity and pushes for reforms; Pakistan makes piecemeal and partial efforts at reform to assuage the IMF; Pakistan exits the program halfway to avoid political fallout; but then, it ultimately rushes back to the IMF in the next crisis. The summary of this can be gleaned in Figure 1 from the various episodes of IMF assistance sought over the past 60 years.

Economists have identified similar cases of politically expedient fiscal cyclicality in other national contexts, such as in the public choice theory of the political budget cycle. According to the theory, a new government will spend generously at the end of its term in order to attempt to win reelection, and after winning it will consolidate or curtail spending since it has already won the current round. Pakistan’s borrow-bust cycle is analogous. Following a crisis, any new government seeks IMF intervention to stabilize the fiscal position by shoring up foreign reserves in exchange for financial reforms. It then makes partial and expedient efforts with a view to keeping the IMF somewhat satisfied without altering the actual structure of the economy. Following a period of seeming improvement in the first year or two, the government then lapses into previous spending habits and the same fiscal structure remains in tact. It also weans itself off the IMF without thoroughly completing the program. In turn, the problems persist for a few years and crisis conditions return, forcing the government to return to the IMF once again. As a result, the government maintains an unhealthy dependence on the IMF and ends up returning periodically, as shown in Figure 1.

However, we can only kick the proverbial can down the road so far, as each new iteration of the borrow-bust cycle is beleaguered by two adjoining problems: a continued burgeoning of the population, and an accumulation of deficits into a ballooning debt portfolio of liabilities. As Pakistan’s population expands relentlessly, the IMF’s austerity agenda becomes a redundant paradigm, as economic growth is far more important than austerity to meet the needs of the teeming masses. The World Bank has come out and said as much: Pakistan’s growth rate is too anemic to meaningfully develop its economy at the current rate of population growth. Additionally, the accumulation of deficit spending culminates in an acute debt burden that has now become an untenable liability for the country. At present, Pakistan’s debt-to-GDP ratio is considered dangerous, as it fuels inflation, stifles productive activities, and prevents public value creation. A substantial portion of the federal government’s expenditures go simply to repay existing debts. Nevertheless, both the IMF and Pakistan have vowed to make the current program into the last program of its kind. But will Pakistan really be able to transition away from IMF dependency this time around?

Figure 1: Pakistan GDP Growth (1960-2025) with IMF programs

Source: IMF, State Bank of Pakistan; Data collected by Muhammad Saad.

The assumption which underpins the hope of a “last IMF program” is that Pakistan will have made sufficient advancements in structural economic adjustment to no longer warrant external multilateral assistance. Pakistan must have made its lopsided economic architecture sustainable, dynamic, and open. This would not merely be a question of fiscal or monetary policy, but also one of governance, sociology, and ethics. Can that sort of hope be expressed at the current juncture? How much success has been achieved to wean us off the original premise of the Borrow-Bust cycle? In the three-year period that has elapsed in the pursuit of stabilization, there is much to credit the government for, but the following structural issues abound:

- The tax/GDP ratio remains low, meaning that indigenous fiscal resources cannot be adequately mustered to shore up the federal balance sheet. Provinces also do not act as revenue-raising units to the degree that they must, hollowing out the centre while leaving much economic activity unaccounted for.

- Exports remain lackluster, and the country depends on remittances to maintain foreign reserves, while keeping a tight check on imports to discourage consumption and investment in an effort to bring the current account balance to heel.

- Foreign direct investment (FDI) is not increasing, and in fact large multinationals have undertaken divestitures of their local presence en masse, leaving the scant existing FDI presence at the mercy of an exodus of disenchanted major players.

- The manufacturing sector is overburdened by taxation and expensive energy costs, making them cost prohibitive and leading them to in turn invest in other countries instead.

- Major sectors of the economy remain untaxed due to their political impunity and their mafioso entrenchment within society, including (but not limited to): agriculture, real estate, and retail. When combined, these sectors amount to the majority of both labor force employment and GDP, and yet they contribute a disproportionately low amount to fiscal effort.

- A tense security situation erodes local and foreign confidence and forces an exorbitant expenditure on constant vigilance and basic security provision, which in turn worsens competitiveness.

- The government’s internal borrowing remains high, adding to the fiscal liability of the government and a continued crowding out of private investment in the economy.

- Erratic weather patterns cause considerable destruction to livelihoods, and scarcely is recovery undertaken for one flooding season that the next deluge arrives.

- The expenditure profile of the federal government remains high, meaning that while tax effort remains low on one side of the equation, the size of government (especially provincial) remains unwieldy and out of proportion with public value provision. Both the revenue and expenditure profiles of each federating unit, as well as the centre, need to be reconciled with public value provision.

As such, it seems unlikely that this will the the last IMF program, unless the IMF itself refused to cooperate in the future. But it too has a business to run as lender of last resort, and it is unfortunately stuck these days with its most dependent clients, including Argentina, Ukraine, and Pakistan. For Pakistan to move off this list, the aforementioned points must be thoroughly addressed, as they comprise the core of the IMF’s expectations. In other words, ending the borrow-bust cycle means sticking to the original commitment and spirit of the EFF that Pakistan and the IMF had signed. In rhetoric, the government remains committed, but the practice of achieving the IMF targets requires more than rhetorical affirmations.

In addition, there is a word of caution about the global economy to be made at this juncture, since it was exogenous shocks (such as the Russia-Ukraine War) that sent the Pakistani economy (as well as other frontier markets) into the original tailspin of 2022-23. The world is more prone to shocks in this decade than in previous ones, with three major crises hitting in quick succession in the last five years alone: Covid-19 (2020-21), Russo-Ukraine Inflation (2022-24), and Trump Tariffs (2025-). It has been very hard for nearly every country in the world to maintain level-headed approaches when barraged with so much, and indeed there is a great socioeconomic disquiet in the world today, with Gen Z revolutions occurring every month in some part of the world. For Pakistan, there are additional burdens of hostile and irresponsible neighboring countries, as well as erratic and widespread inundations due to climate change. We do not recover from a previous year’s floods before the next year’s floods ensue. This makes the task of economic managers all the more difficult, and the hope of disburden from the IMF all the more remote.

Nevertheless, having demonstrated an impressive stabilization effort over the past three years, it is important to stay the course and continue wholeheartedly with the reform effort. The issue is not that the reforms are burdensome (which they are), but rather that we have shunned the struggle in the past; hence, our task has become ever harder with time. What must be different in the current instance is to not succumb to the temptation off waving the IMF an early goodbye while falling short of the structural reform effort that still lies ahead. Therefore, even as global and local crises ensue in unabating succession, there may be a legitimate need to return to the IMF in the future, but we must minimize that risk by strengthening our economy through fiscal responsibility and reform. Otherwise, every future instance of IMF intervention will be all the more difficult to absorb.Dr. Usman W. Chohan is Advisor (Economic Affairs and National Development) at the Centre for Aerospace & Security Studies, Islamabad, Pakistan. He can be reached at [email protected]