Having a conceptual framework in mind allows one to apply existing knowledge to unfamiliar scenarios, adjusting the framework as new data comes to light. Since CASS’ inception (2018-19) I’ve worked to build one such conceptual framework (a working model) in my mind for Pakistan’s macroeconomy, as part of an effort to grapple with its complexities, including its challenges such as the sizable informal sectors, inconsistent data sources, and not to mention: the extreme volatility of the global economy in that period. Thus, at a seminar conducted recently by the National Institute of Maritime Affairs (NIMA) and the Institute of Strategic Studies (ISSI) which focused on the maritime and port sectors, I was able to deploy my working framework to absorb and contextualise the specific challenges discussed.

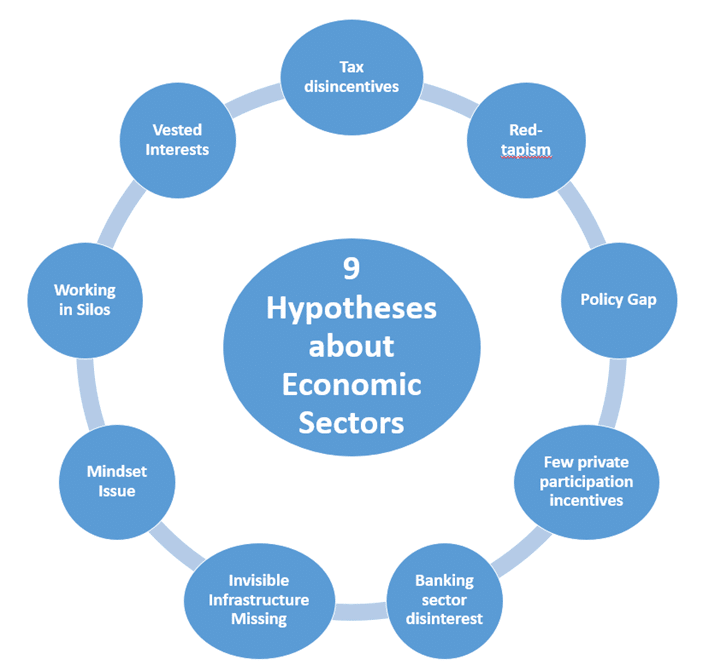

During my participation as a discussant, I presented nine hypotheses about Pakistan’s broader political economy, asserting that these macro-level challenges extend across sectors, including the maritime and port industries. In other words, by overlaying my existing macroeconomic observations onto sector-specific challenges, I was able to draw parallels between the issues NIMA experts discussed and the broader economic afflictions that Pakistan faces. I enumerate the nine hypothesis that applied equally to the maritime and port sectors as to the economy at large, and they are also depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1: 9 Hypotheses about Economic Sectors

- The tax system disincentives the sector’s growth. As my previous research has shown, the nation’s tax system violates all the principles of an ideal tax structure, consisting of fairness, neutrality, efficiency, simplicity and certainty. An example of this in the maritime sector is how, beginning in 2018, there was to be 0% tax on new vessel purchases, but in 2021 an ad hoc inclusion in the Finance Bill slapped a 33% tax on any such purchase. How much revenue was raised from this? No vessels were purchased in that year or since.

- The bureaucracy stifles development (Red-tapism). There is now a large body of research by entities such as PIDE, PRIME, and CASS indicating that the public sector’s colonial structure is antithetical to business activity, and the deployment of generalist administrators rather than subject-matter specialists and technocrats leads to policies and practices that do not speak to the requirements of otherwise very narrowly specialised sectors. This is no less true for the generalist bureaucrats dealing with maritime affairs, according to practitioners facing bureaucratic encumbrances.

- The policy is outdated or unimplemented. In many sectors, policies are either outdated or remain unimplemented (or they may simply not exist!), leading to stagnation in economic development. For instance, trade and industrial policies have not kept pace with modern advancements, leaving many sectors lagging. Pakistan’s maritime sector policy reflects this, as it was designed to spur growth but remains largely unimplemented due to lack of inputs from practitioners, buy-in from stakeholders, and government interest. For instance, the policy called for the modernisation of port infrastructure and fleet expansion, but two decades later, these goals have not been achieved. Consequently, port congestion and inefficiency persist.

- There are few private incentives for participation: There is a lack of clear incentives for private sector participation in most industries in Pakistan, particularly in sectors where large initial capital investment is required but returns are uncertain or hindered by bureaucratic hurdles. This is no less true for the shipping industry in Pakistan, which suffers from a lack of private sector involvement due to minimal financial incentives (including tax breaks). Unlike other major Asian economies, which offer subsidies for shipbuilding and fleet expansion, Pakistan’s private sector sees little reason to invest in these areas, and this is particularly evident in the lack of local shipbuilding initiatives, where as a result, the country is forced to rely on foreign ships.

- The banking sector disinterest: Pakistani banks are often hesitant to finance sectors with long gestation periods, focusing instead on short-term, high-return ventures like consumer financing (at best), or much rather on lending to government at an extortionary risk-free rate. The maritime sector, including shipbuilding and port infrastructure development, requires long-term financing, which Pakistani banks are unwilling to provide. The result is that companies seeking to upgrade port infrastructure or purchase new vessels face prohibitive financial barriers, leading to dependence on external funding sources or outdated technology.

- The key invisible infrastructure is missing: For many sectors, although the visible infrastructure may exist and be quite good (e.g. roads and highways), the invisible infrastructure (on which votes cannot be gained) remains missing. In the port sector, this is a particularly pressing issue because of the draft of the ports required to bring in large-scale ships (at least 16m). This is not evident on the surface, but dredging and deepening the ports is necessary to allow large volume freight to enter. Furthermore, the conversion of cargo to railways is low, while the trucking queue is monstrously long at the ports (i.e. the movement from out of the port is highly inefficient). In addition, Karachi is dumping 25,000 tonnes of waste per day into the sea, making the draft shallower with each passing day. These are elements of infrastructure which are not immediately visible but have a very severe impact on the efficiency and costs incurred in the sector.

- There is a mindset issue: The majority of Pakistanis hail from either the floodplains or the hills & mountains, with no concept of seafaring life. This has a very severe albeit hidden impact on policy making in Pakistan, because stakeholders do not view the sea as part of their immediate environment or lived experience. The sea-gazing mindset is one that would need to be cultivated through awareness programmes.

- Government departments are working in silos: Interdepartmental cooperation is rare, and ministries and government bodies often work in silos without coordination, leading to fragmented policy implementation and missed opportunities for synergies. An example from the maritime sector highlighted by experts was in having the Pakistan National Shipping Corporation (PNSC) work closely with Pakistan State Oil (PSO) for oil movement, which would have billions of dollars of annual impact and savings in foreign currency.

- Vested interests hold sway: By and large, there are powerful interest groups in economic sectors that often control policy directions, preventing reforms that would benefit broader economic development and the national interest. In the maritime industry, vested interests are found in import lobbies, blocking reforms that could enhance competition and efficiency.

In essence, even without the specific examples provided by the other experts at NIMA, I would have deduced the existence of these problems because they are widespread across every sector of the economy. As a discussant, my central argument was to emphasise the interconnectedness and ubiquity of these issues throughout all sectors, be it ports, healthcare, aviation, education, agriculture, or anything else. I argued that these are not isolated challenges but symptoms of a deeper, systemic issue that affects much of the developing world, hampering its ultimate progress. No sector can be considered in isolation; the same structural inefficiencies permeate all. Therefore, one cannot expect isolated ‘pockets of excellence’ to transform the economy. Instead, progress requires addressing the root causes and lifting all sectors simultaneously if national development is to be achieved.

Dr Usman W. Chohan is Advisor (Economic Affairs and National Development) at the Centre for Aerospace & Security Studies, Islamabad, Pakistan. He can be reached at [email protected].