Amidst transforming regional security dynamics, India reinforced its eastern flank by establishing three fully operational military stations at strategic points around the ‘Siliguri Corridor’ near the India-Bangladesh border. The new bases include the Lachit Borphukan Military Station near Dhubri in Assam along with two forward bases at Chopra in West Bengal and Kishanganj in Bihar. Indian Army also reviews a fourth station in Mizoram as part of extended defence arc around the Siliguri corridor. Amidst deteriorating ties with Bangladesh, India’s fortification of its eastern frontier signals the opening of a new strategic front, which demands vigilance. These advancements followed the ouster of pro-Indian, Sheikh Hasina’s government in 2024, evolving regional dynamics and Dhaka’s transformed military posturing.

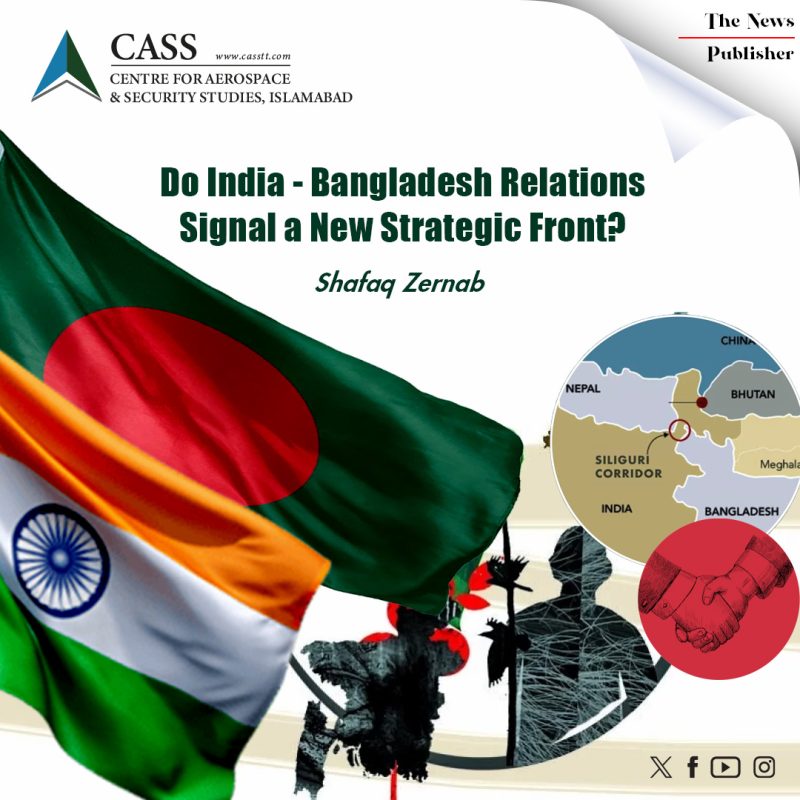

The Siliguri Corridor, colloquially known as ‘Chicken Neck,’ holds profound significance for India. Located between Nepal, Bhutan and Bangladesh, it is a 22 kilometres narrow strip that links mainland India with its 7 eastern states, (including Assam) hosting a population of 49 million. This geostrategic chokepoint is the primary transit passage for trade, military and civilian supplies. It is India’s most critical strategic vulnerability as any disruption to this passage could sever northeast from mainland India.

The Siliguri Corridor has already been defended by Trishakti Corps with Rafale jets, Akash and S-400 air defence and Brahmos missile systems. However, the addition of forward bases signals a more proactive Indian strategy. The defining feature of this current buildup located near Bangladesh’s border is its integrated nature, that sets it apart from previous border infrastructure. These new stations equipped with advanced ISR capabilities enhance India’s ground-based operational readiness. These stations act as a strategic triangle providing overlapping coverage of the corridor with minimal time frame directives focused on rapid operational deployment. Operationalising these bases marks a departure from India’s defensive posture of border management to rapid response-offensive capabilities, indicating a reorientation of Indian military’s threat perceptions about securing its periphery. This heavy militarisation suggests that India’s fortification of Chicken Neck may become a flashpoint for high-tech complex military platforms.

This development aligns with the broader geopolitical context as India has expressed concerns regarding Dhaka’s interim government’s growing engagement with China and Pakistan. As elections draw near in Bangladesh, recent high-level meeting of Yunus with Pakistan’s military leadership has heightened Indian anxieties. Bangladesh has also revamped its military procurement. Yunus’ administration has disclosed plans to acquire Chinese J-10C as well as setting up an industrial base in Dhaka for joint drone production with Beijing. Similarly, Pakistan proposed to sell JF-17 Block C Thunder jets to Dhaka. The Bangladesh Army has acquired the Chinese-built SY-400 short-range ballistic missile (SRBM) system.

Bangladesh also plans to revive a WWII era base near Lalmonirhat with Chinese assistance. It includes the near completion of a large hangar capable of parking multiple fighter aircraft. Helicopters and light aircraft are reportedly conducting regular sorties from the base, compelling India to reinforce counter measures. Recently, Bangladesh Air Force (BAF) has also signed a letter of intent with Italy’s Leonardo S.P.A to buy Eurofighter Typhoon multi-role combat aircraft as part of its modernisation plans.

However, given the stark power asymmetry between Dhaka and New Delhi, Bangladesh has a sound rationale to modernise its defences. India’s new military footprint near Bangladesh’s border inadvertently heightens its security dilemma. Historical precedents from Russia’s Crimean facilities, to China and India’s logistical and military buildup suggest that these developments are like stacking dry kindling along a neighbour’s fence. The act can be disguised as mere collection of firewood, until the political match is lit, providing the fuel for rapid escalation. Moreover, given Dhaka’s constrained strategic depth, absence of any bilateral protocols limiting Indian military deployments exacerbates its sense of vulnerability .

Bangladesh is also facing deportation issue of alleged illegal migrants from Indian Border Security Forces (BSF). In an unexpected turn of events, anti-India sentiments resurfaced in Bangladesh. Recent assassination attempt of a prominent figure of July uprising, Sharif Osman Hadi (who died in the hospital in Singapore) by alleged Indian assailants has sparked violent protests in Bangladesh. Amidst the massive public outrage, leader of Jatiya Siramek Shakti, Mutaleb Shikder was also shot but survived the injury. Protestors are calling for home advisor’s resignation. The political stakes are further heightened by the fact that one of the leaders was a prospective candidate in the upcoming elections. As the pressure mounts on the interim government, this violence serves India’s interest to eliminate a direct internal political threat.

India is unwilling to cede control over Bangladesh which it has long exercised through the client regime of Sheikh Hasina. With that influence significantly lost in the 2024 uprising, India is resorting to coercive measures by militarising the Siliguri Corridor and alleged interference in Bangladesh’s internal matters. Yet, each move acts as a political catalyst pushing Dhaka further away from New Delhi. India treats Bangladesh as mere corridor to be controlled, rather than a sovereign neighbour to engage with. Dhaka has explicitly demanded to hand over Sheikh Hansina. Yet New Delhi provides a platform to Hasina for media appearances. This shows a lack of political will to resolve the matters and compounds Bangladesh’s grievances. Far from neutralising a threat, India is assembling one on its doorstep which has regional implications. The path forward cannot be built on bunkers but diplomacy before India’s front becomes a regional frontline.

Shafaq Zernab is a Research Assistant at the Centre for Aerospace & Security Studies (CASS), Islamabad, Pakistan. The article was first published in The News. She can be reached at [email protected]